the worst of all

collaborative research, 2025

La peor de todas (The Worst of All) is a process-based research project by Chris Luza and Isaac Ernesto, which develops a transdisciplinary methodology for visual production and speculative fiction as a means to rethink the relationship between technology, colonial memory, and imagination. The title references Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s self-description as “the worst of all,” reclaiming her gesture of resistance against the patriarchal and colonial hierarchies of her time (sXVII) as an entry point for critically engaging with Artificial Intelligence (AI). Throughout its development, the project has unfolded through workshops, speculative exercises, and collaborative research, culminating in the exhibition held from November 13 to December 13, 2025.

Below is the curatorial text written by Carlos Zevallos Trigoso, which situates the exhibition within the broader conceptual and political questions that frame La peor de todas.

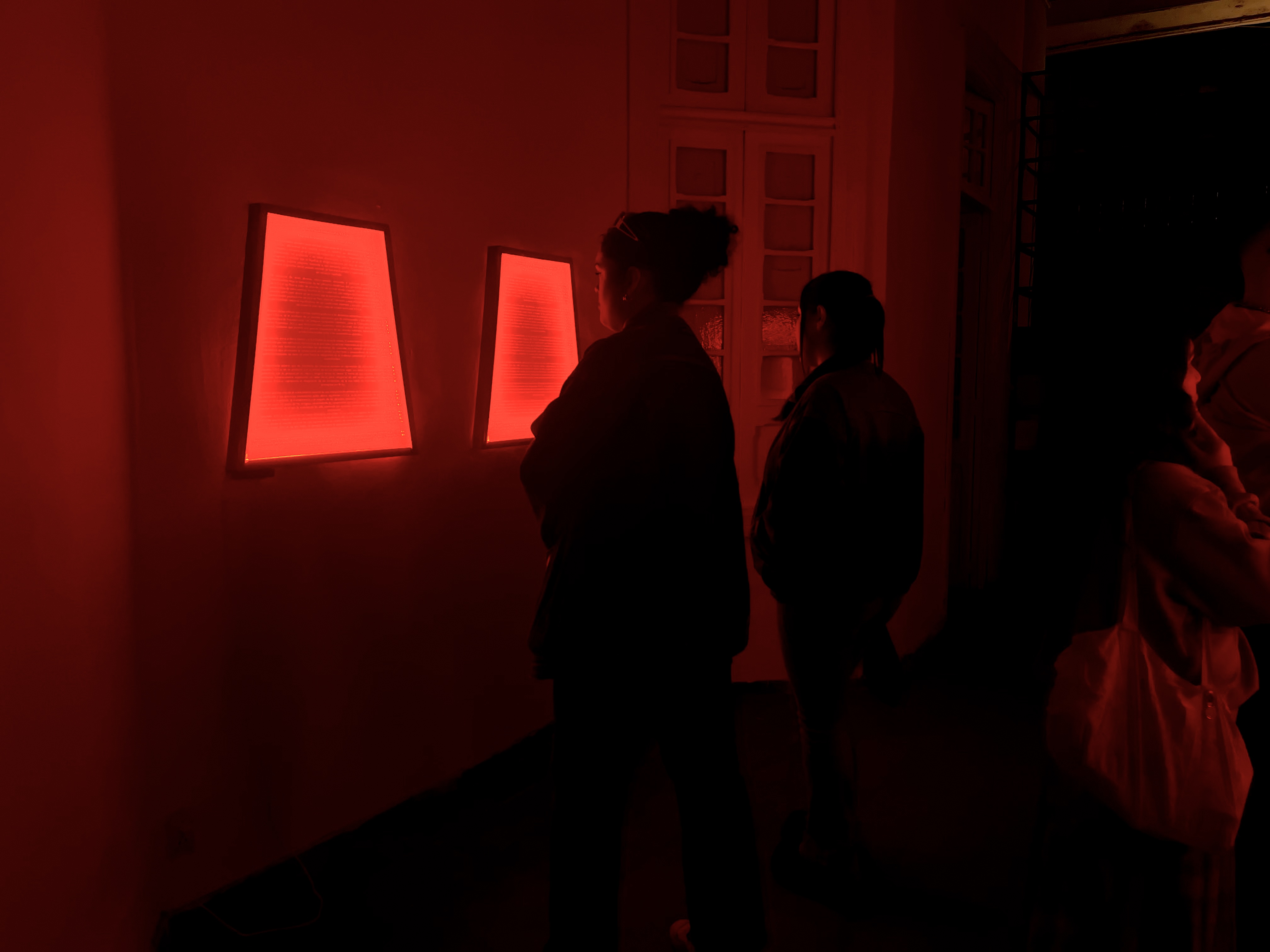

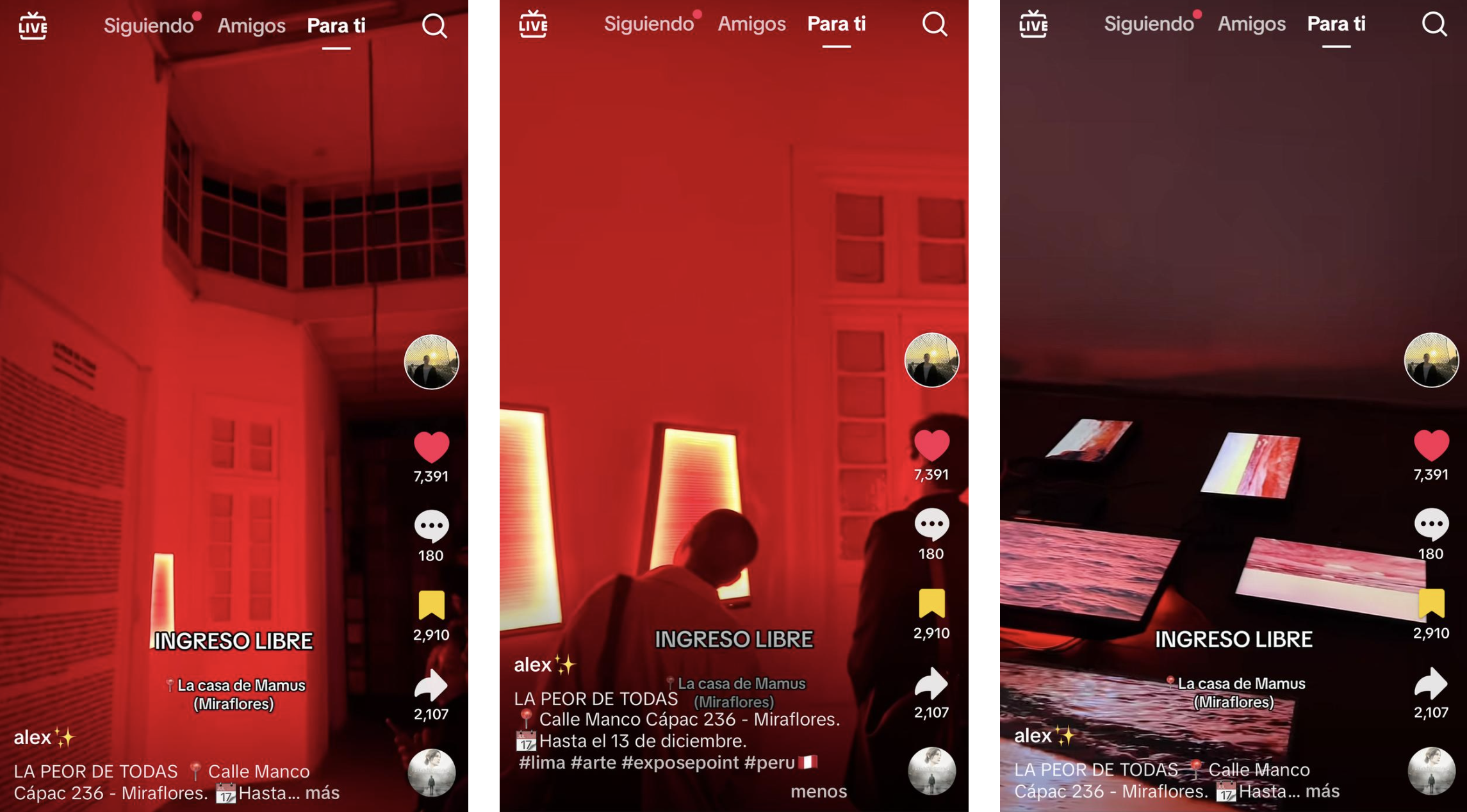

La peor de todas — Exhibition at Casa de Mamus

“This exhibition emerges as the result of an artistic and methodological research project developed by Chris Luza and Isaac Ernesto, recipients of the Visual Arts Production Grant from the Ministry of Culture of Peru. The project arises from a negotiation with the institutional expectations that typically shape such funding: the demand for social impact and the preference for productions that do not overly trouble the structures that sustain them. In response, Chris and Isaac shift the emphasis away from the artwork as a final product and toward the systematization of research–creation processes, proposing that methodological work is itself a form of artistic production.

Thus, the project focuses on developing strategies to systematize the emerging relationship between art and technologies linked to generative artificial intelligence, interrogating both its potential as a tool for research–creation and the frictions that stem from its fundamentally capitalist and neocolonial origins. The proposal directly addresses the question of the relationship between artistic creation and generative AI at a historical moment in which narratives proliferate that frame AI as a threat to human creativity—this supposedly exceptional faculty that would distinguish us from machines.

A common response to this horizon is the celebration of manual, analog, “artisanal” forms of work as the last bastion of the properly human in the face of total automation. However, it is necessary to ask whether this defense of “the human” merely reproduces the hierarchies and exclusions that have historically shaped that category. Critical perspectives on Western liberal humanism (Braidotti) have emphasized that the figure of “Man” as a universal subject has always been a normative construction that excludes that which is not male, white, European, heterosexual, and property-owning. Likewise, postcolonial studies have shown how the category of “human” was systematically denied to colonized peoples for centuries, legitimizing their enslavement and exploitation. To reclaim “the human” against the machine risks reinstalling the very onto-epistemic hierarchies that underpin both capitalist productivism and the colonial difference.

This does not mean surrendering uncritically to the multibillion-dollar corporations that control the infrastructures of generative AI—corporations whose business models rely on massive data extraction, the labor precarity of data annotators in the Global South, and the consolidation of technological monopolies. Rather, it calls for a simultaneous distrust of both the techno-solutionist promises of these platforms and the discourses that urge us to rescue a supposedly threatened human essence, as if that essence had not already been a category of domination.

In this project, Chris and Isaac adopt a position of ambivalence toward generative AI technologies. They approach them as something that operates simultaneously as remedy and poison, without being able to determine in advance which of these dimensions will prevail. This radical ambivalence requires inhabiting the discomfort of not knowing whether these tools function as instruments of emancipation or control, of creation or automated reproduction. Generative AIs operate precisely in this register: they are tools that can amplify imaginative capacities and facilitate research processes, but also devices that consolidate corporate power, reproduce colonial and racial biases sedimented in their training data, and threaten to intensify the precarity of creative labor.

What we encounter in this exhibition is an installation titled “V.O.C.e (Versatile Organic Chemical Enterprise)”, which is also the name of a fictional recreational drug company critically reimagined from the history of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or V.O.C.), responsible for the ferocious colonial exploitation of spices in the Maluku Islands in eastern Indonesia between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In this futuristic version generated with AI, V.O.C.e manufactures recreational drugs made from nutmeg, clove, and coca leaf—substances historically coveted in Europe.

The conceptual operation is revealing: the “spices” that fueled Dutch colonial extractivism in Indonesia are speculatively combined with coca leaf, which has its own history of colonial extraction in the Andes. What emerges is a dystopian future in which colonial structures have not been overcome but displaced and reconfigured: the center–periphery logic persists, the extraction of resources from the Global South for the consumption of the North continues, except now the commodities are psychoactives rather than spices. This future is not a warning about what could happen but a way of rendering visible how the future is already being colonized by the same grammars of domination that shaped the past. V.O.C.e is not an imaginary company located in a time to come—it is the contemporary unfolding of extractivist logics that never ceased to operate.

Alongside this project, the exhibition also includes three folders containing documents produced in the workshops “Imagining Critical Futures”, which were speculative fiction spaces conducted in Iquitos, Trujillo, and Huamanga. In these workshops, groups of participants worked with generative AI to create speculative stories about the future of their territories.

The proposal does not emerge from nowhere; rather, it is activated through what already pre-exists in the massive corpora of texts and images on which these platforms were trained. Generative AI models have been fed global cultural archives saturated with colonial histories, extractivist narratives, apocalyptic imaginaries, and structures of epistemic violence. When we ask an AI to imagine the future, or to generate stories about corporations, colonialism, or drugs, we are in fact activating these sedimentations: AI does not invent from scratch—it reconfigures and recombines patterns that already inhabit its training layers.”

- Carlos Zevallos Trigoso

Speculative fiction workshops — Huamanga, Iquitos & Trujillo.

The second phase of the project, the Speculative Fiction Workshops were held in Iquitos, Ayacucho, and Trujillo, where participants collectively imagined critical futures and constructed shared alternative chronologies. The workshops took place in three different community and cultural spaces: the César Vallejo School in Huamanga, the Museo de Arte Amazónico in Iquitos, and Paijaaaaaaan in Trujillo, in collaboration with the Museo de Arte Moderno de Trujillo (MAM).Across the three workshops, participants worked primarily with existing forms of community and social organization, using them as foundations to imagine collective modes of resistance and reconstruction. These imaginaries often sought to reconstitute bonds of communal life that challenge the stability of the colonial modern project. At the same time, the workshop results made visible the ways infrastructural algorithms operate when projecting themselves into the future—revealing how colonial matrices continue to reproduce themselves through racial, class-based, and gendered conditioning.

Huamanga — After the 2075 Collapse

In Ayacucho, participants developed a fiction set after the global collapse of 2075—marked by the bombing of major world capitals and the fall of Lima due to a zombie occupation. Autonomous forms of organization began to emerge throughout the region. In Huamanga, the first assemblies were convened through graffiti on walls and streets reading: “Asamblea General de Organización.”

From these gatherings arose new structures of care, including the Colectiva de Madres Cuidadoras, which led the reforestation of the city, water harvesting, and the cleansing of acequias as both ritual and economic practices. Their work also gave rise to Cholita Ruda, a space for collective and horizontal childcare, symbolizing a new mode of community grounded in equity and affection.

Faced with dissent and internal tension, the assemblies replaced punishment with reparative forms of reintegration based on care and dialogue. What ultimately emerged was a nameless society—a living network recognized through gestures rather than titles, through rounds, regrowth, and murmurs. A community refusing the notion of nationhood yet flourishing in acts of shared care.

The complete archive is vailable through this link.

Iquitos — The 2035 Amazon Summit

In Iquitos, participants imagined the 2035 Amazon Summit of Loreto, where Indigenous leaders and regional governments meet for the first time to envision a future based on ecological sovereignty and territorial justice. From figures such as Jorge Pérez Rubio to Nemonte Nenquimo, Amazonian voices consolidate a historic pact prioritizing life, autonomy, and the responsible use of natural resources.

Yet the initiative faces opposition from extractive corporations whose interests are threatened. Amid media disputes and unexpected alliances, the summit marks the beginning of a new decade of continental organizing leading toward 2045: the time of the forest.

The complete archive is vailable through this link.

Trujillo — Before and After the 2048 Reset In Trujillo, the workshop imagined a prelude to the 2048 Reset. Before the collapse, the Alianza Vigías de Chan Chan—a conservative technoscientific-spiritual elite—attempted to preserve the old order, fearing that the earth might “forget how to remain solid.” Their failure gave rise to the Gran Huayco, a total collapse that dissolved cities, certainties, and hierarchies.

In Paiján: Memory of the Future, the Natural History Museum of Paiján reconstructs this transition, showing how humanity learned to mutate alongside the desert. Among Aerocondors, Viringos, and Eco-Oceanics, the narrative celebrates adaptation as a vital principle and warns that survival lies not in resisting change, but in transforming with it.

The complete archive is vailable through this link.

CHRIS LUZA - PERÚ. - 2025